1. The Meliès Moon

For me, the artistic work of Georges Méliès represents not only the birth of cinema as we still know it today, and the purest form of technical and artisanal ingenuity, but also an extraordinary and moving life story: glory, downfall, and an almost heroic rebirth.

I first fell in love with him when, during a beautiful exhibition in Paris dedicated to the dawn of cinema, I saw a photograph portraying him behind the counter of a small shop selling sweets and mechanical toys objects he himself built and repaired at Montparnasse train station. A neighborhood particularly dear to me, where my father lived for over forty years.

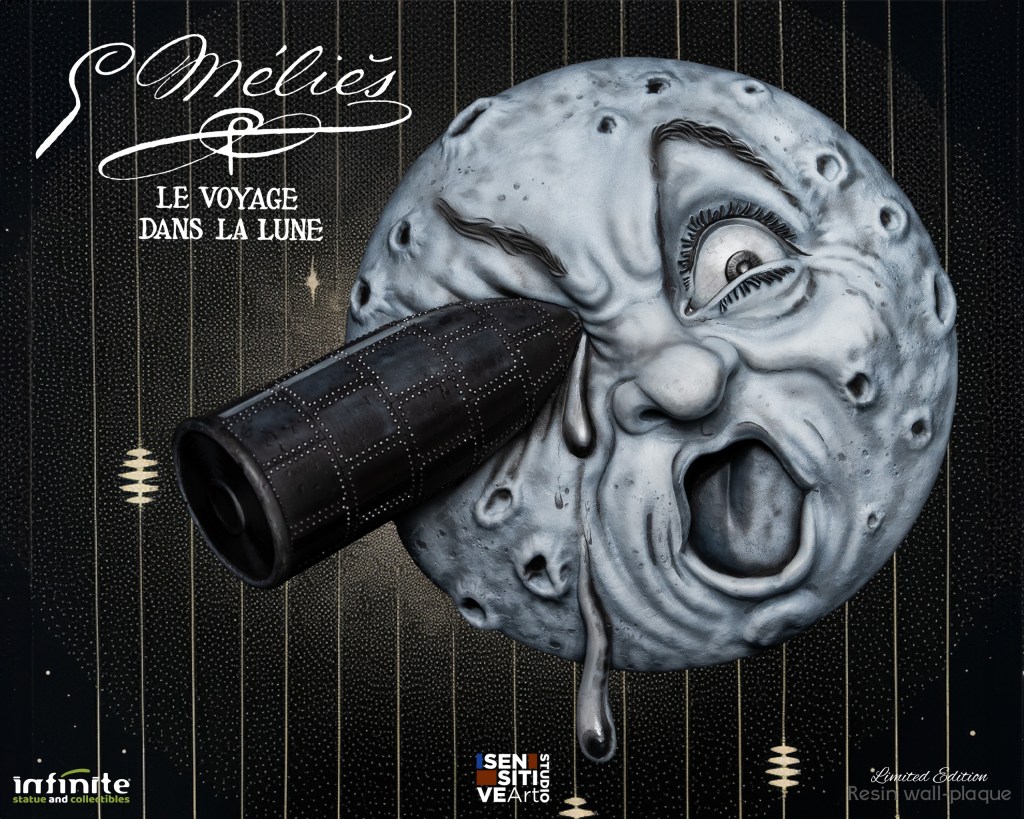

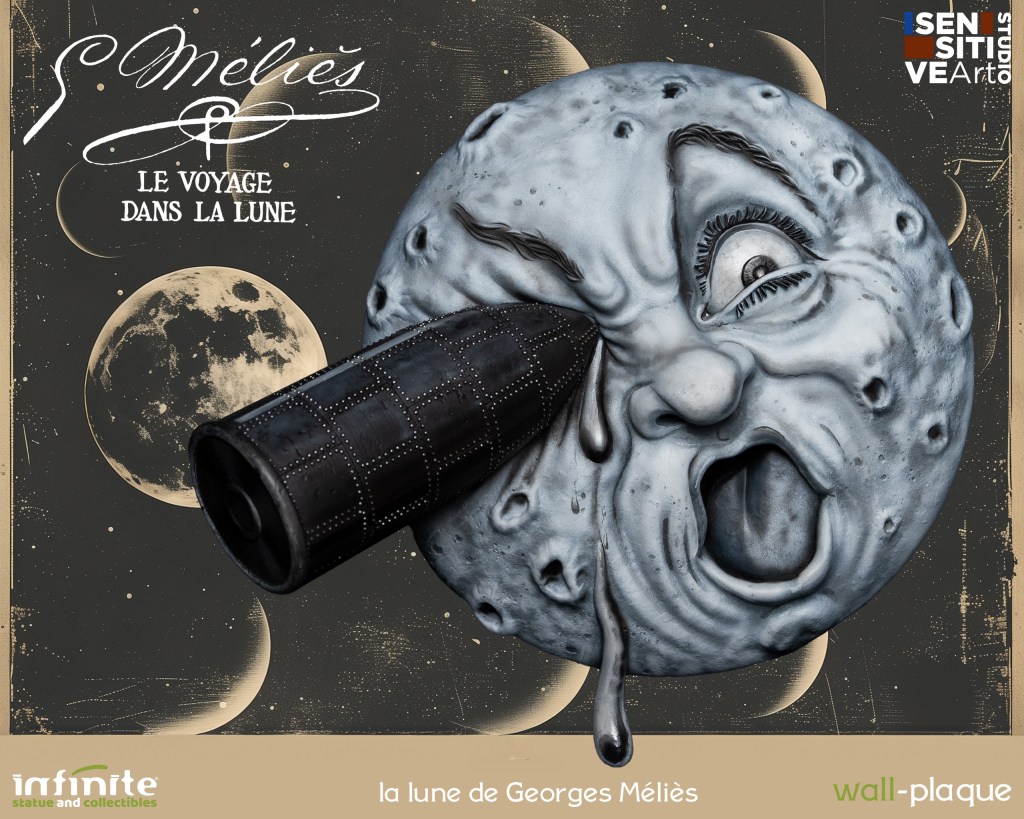

Back in 2010, I had already created a Méliès Moon: a reproduction of the famous frame in which the rocket launched from Earth strikes the Moon in the eye. On that occasion, the choice was to offer an almost photographic interpretation of the image, with the only liberty being a slightly less “angry” expression than the one shown in the film. At that time, the sculptor worked entirely by hand no digital tools, no 3D. This gave the piece a truly artistic touch, something that has been gradually lost unless deliberately pursued. Mauro Gandini did an excellent job, and the statue (or rather the wall-plaque, as it’s called in commercial jargon) was such a success that two years later I designed and produced the same version, this time enhanced with a beautiful fluorescent effect, created exclusively for the American market.

So, when I decided to launch this new venture, I began precisely with one of the sculptures I cherished most. At the same time, I didn’t want a mere repetition, but a new interpretation. I chose as the basis one of the drawings that Méliès himself created in 1933 (just three years before his death), at the request of the newly founded Cinémathèque Française. Once again, the sculptor (Daniele Angelozzi) carried out extraordinary work, faithfully respecting, as I required, the “structure” of the drawing, while demonstrating how modern digital sculpture can also serve as a highly artistic medium, even without the use of physical matter. To this, we must add the incredible contribution of the painter (Dario Barbera), who perfectly captured the style of the original drawing with its multiple shades of black and white astonishingly rich in color.

With this first project, I initially feared it might not receive the same positive response, since it represented a kind of “return to the origins” of what Infinite Statue once was: the courage to go against the tide of the mainstream 3D statue market, producing works inspired by a forgotten, outdated cinema destined for true connoisseurs. In the cold language of commerce: a niche. I feared that audience might no longer exist. I was wrong. The swift sell-out of the Moon was proof of that.